Let’s help you

plan your journey

Explore responsibly, discover offbeat places, guided by locals, rooted in culture.

Let’s help you

plan your journey

Explore responsibly, discover offbeat places, guided by locals, rooted in culture.

Soumen

A slow traveller, road trip enthusiast, Soumen travels to understand how places breathe beyond maps and itineraries. A road tripper at heart, he finds meaning in country roads, small conversations, changing landscapes, and the quiet stories that unfold between destinations.

The First Places I Met Were on Screen and on Pages.

Long before I stood at some of the places I now remember vividly, I had already met them in stories. Sometimes through the flicker of a cinema screen. Sometimes through quiet pages of a book. These early encounters did not feel like imagination alone. They felt like introductions.

A desert battlefield, a cliff above the sea, a frozen blue lake, a forest alive with silence, a hill town wrapped in gentle nostalgia — these places entered my life not as destinations, but as emotions. When I eventually travelled, I did not feel like I was arriving for the first time. I felt like I was returning to something that had already settled quietly inside me.

Longewala entered my life through the film Border. I had never seen a desert stretch that wide or silence that heavy. The film did more than show a battle. It showed isolation, fear, courage, and the weight of a place that barely appears on most maps.

When I later learned about the real Longewala, it did not feel unfamiliar. The sand, the vastness, the sense of distance — all of it already existed in my imagination. The place had already shaped an emotional memory long before it became a geographical location.

Chapora Fort felt like freedom before it ever became a location for me. Dil Chahta Hai made it less about the fort and more about the feeling of standing still while life unfolds ahead. Friendship, hesitation, change — all framed against a cliff by the sea.

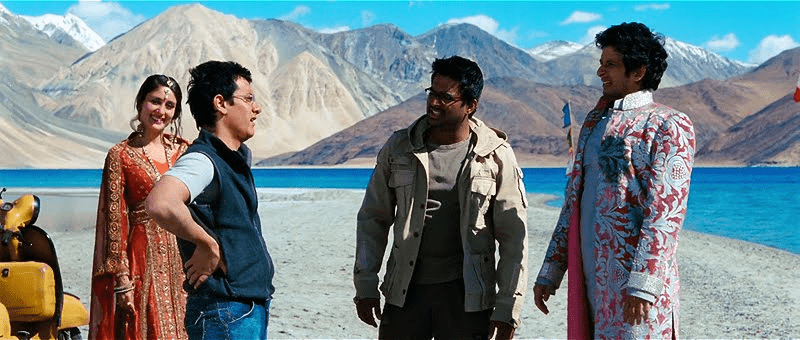

Pangong Lake arrived through Three Idiots. A blue so unreal it felt fictional. The place became a symbol of release, reunion, and quiet arrival after restlessness. Long before I ever thought of Ladakh as a region, Pangong already existed in my mind as a feeling.

Forests and hills entered my world through books before roads ever led me there. Jim Corbett’s writing made the jungle feel alive long before I understood its geography. Ruskin Bond’s Mussoorie was not a hill station — it was childhood, memory, loss, rain, and quiet resilience.

These places felt less like travel goals and more like familiar companions waiting patiently somewhere beyond the page.

Some places remain known only through stories, yet they feel deeply real. Afghanistan through The Kite Runner was not a country on the news. It was friendships, guilt, migration, broken homes, and lingering hope.

Istanbul through The Museum of Innocence became lanes of obsession, museums of memory, tea cups holding years of emotion, and streets that carried longing more than crowds.

I have not visited either place. Yet they have already shaped how I understand distance, belonging, and time.

Macondo from One Hundred Years of Solitude is not on any map. Yet it is one of the strongest places that has ever stayed with me. Rain that falls for years. Generations repeating mistakes. Love that lingers after death. A village carrying the weight of memory like a living being.

Macondo taught me that destinations do not always need coordinates. Some live only in the mind — and still shape how we see the real world.

Not all journeys begin with tickets. Many begin with stories. Films and books do not just show places — they give them context, emotion, conflict, beauty, and contradiction. When travel finally happens, it does not begin from zero. It begins from memory.

Some destinations arrive as landscapes. Some arrive as longing. Some arrive as unfinished conversations with characters that never existed. And some arrive only to remind us that travel is not just movement through space — it is movement through imagination, memory, and understanding.

Also Read:

Yes. Many travellers decide to visit places after seeing them in films. Cinema creates emotional familiarity, which often turns into real-world curiosity and travel decisions.

Yes. Books usually add depth, inner conflict, social context, and emotional layers that visuals alone cannot always capture.

It can be limiting if travellers expect the real place to exactly match the fictional version. Stories should be entry points, not final definitions.

Because emotional memory often forms before physical experience through repeated exposure in films, books, and cultural conversations.

Yes. Fictional places like Macondo shape how people think about time, life, relationships, and landscapes — even without physical geography.

Yes. It creates slower, more reflective travel, where places are felt rather than rushed through.